Deal Summary

In February 2007, after 25 years of working its way to the top of real estate private equity, The Blackstone Group, led by Jonathan Gray, acquired Sam Zell’s Equity Office Properties Trust (EOP) for $39 Billion (including debt). At the time of the buyout, Equity Office was the country’s largest owner of office buildings with over 500 buildings totaling over 100 million square feet across many markets including Los Angeles, Seattle, San Francisco, New York City, Washington D.C. and Boston. Although the timing of Blackstone’s acquisition could have led to its downfall (2007 was immediately before the burst of the real estate bubble), Blackstone took advantage of the real estate bubble by unloading most properties acquired through its acquisition of EOP within a few months after its acquisition. By the time the market entered a recession in 2008, Blackstone was left with a portfolio of high quality, well-located office buildings which it was confident would fare well through the upcoming recession. Almost 10 years after the buyout, Blackstone estimates it will triple its initial investment and Blackstone’s buyout of EOP is widely considered to be one of the most successful real estate private equity deals of all time.

During an upcoming series of blog posts, we’ll walk through the entire deal including:

- Part 1: Background of both companies, negotiation leading up to the buyout, and closing

- Part 2: Analysis from Blackstone’s perspective of the property-by-property sell off of EOP’s portfolio

Let’s start Part 1 with a background of the buyout:

Background of Blackstone’s Real Estate Private Equity Business

In 1985, with just $400,000 of seed money, Steven Schwarzman and Pete Peterson founded The Blackstone Group, initially advising corporations on mergers and acquisitions. Since its inception, Blackstone’s growth can best be described as calculated, strategic, and spurred by opportunities presented during market downturns. In 1987, following a decline in the stock market, Blackstone raised $800 Million in its first fund and thereby began its corporate private equity line of business. In 1992, in the midst of the Savings and Loan Crisis, Blackstone founded its real estate private equity line of business, with John Schreiber as the co-founder and head of the division. In addition to John Schreiber, notable early employees in Blackstone’s real estate business included Jonathan Gray and Kenneth Caplan. Gray, who began his career at Blackstone in 1992 at just 22 years old, worked immediately under Schreiber in a position that would expose him to a wide range of real estate deals and groom him to take on some of the largest, most complex real estate acquisitions later in his career. From its early days, Blackstone implemented its “buy it, fix it, sell it” philosophy in operating its real estate business, seeking to acquire quality assets in strong markets at prices amounting to less than the property’s replacement cost. Over its first 20 years, Blackstone experienced major success, with its real estate private equity business outpacing its other divisions and making up a continuously increasing share of the parent company’s total profits.

In 2005, upon Schreiber’s departure from an active role in Blackstone’s real estate business, Gray and Caplan were promoted to co-heads of Blackstone’s real estate business. Under Gray’s and Caplan’s leadership, Blackstone further expanded its real estate business by raising over $7 Billion in investor funds during 2006, more than the combined amount of all the funds its real estate business had raised in the previous 14 years since the inception of Blackstone’s real estate line of business. In 2007, Blackstone would surpass its 2006 funds by raising an additional $10.9 Billion for its real estate private equity operations. With many billions of dollars at its disposal, Blackstone needed to find a way to deploy huge amounts of capital in a way that would return substantial profits to investors.

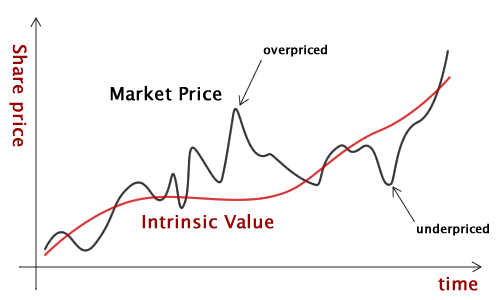

Gray and Caplan scoured the market and noticed an opportunity in REITs (real estate investment trusts), or publicly traded investment vehicles which own real estate assets and pay out dividends using income from the REITs assets. Gray and Caplan felt that many REITs were undervalued and prices of the REITs hadn’t increased sufficiently in light of the run of real estate values in the early 2000s. Taking it a step further, Gray and Caplan thought that they could even pay huge premiums on the publicly traded prices of REITs (in some cases 30% above the publicly traded price), pay billions of dollars in interest on borrowed money, pay billions of dollars of transaction fees (commissions, transfer taxes, attorney fees, etc.) and still have enough room to profit on the resales of the REIT’s assets.

During 2006, Blackstone embarked on a REIT buying spree which included the following acquisitons:

- During February 2006, Blackstone acquired MeriStar Hospitality Corp for $2.6 Billion, which represents a 20% premium to MeriStar’s stock price before rumors surfaced about a buyout. At the time of the acquisition, Meristar owned 57 luxury hospitality properties across the country.

- During March 2006, Blackstone and Brookfield Properties jointly acquired Trizec Properties for $8.9 Billion. At the time of the acquisition, Trizec owned 40 million square feet of office complexes in the United States and Canada.

- During March 2006, Blackstone acquired CarrAmerica for $5.6 Billion. At the time of the acquisition, CarrAmercia owned 26 million square feet of office properties in Los Angeles, Dallas, and Denver.

Considering that private equity real estate transactions typically involve leverage, Blackstone’s buying power ranged anywhere from 3 times to 10 times the $17 Billion of funds it raised during 2006 and 2007. Even with three major REIT acquisitions during the first few months of 2006, Blackstone would still need to seek out many investment opportunities in the coming years in order to deploy all of its capital.

Background of Equity Office Properties Trust

Sam Zell (born Shmuel Zielonka) began his involvement in real estate when he founded a student housing management company at 20 years old while studying at the University of Michigan. While at the University of Michigan for undergrad and law school, Zell met Robert Lurie, an engineering major, through his fraternity. Upon graduating and leaving Michigan, Zell sold his student housing management business to Robert Lurie and extended an invitation for Robert Lurie to later join him in Chicago, where Zell would be “playing on a big field in real estate,” as recounted by Zell today.

Three years later, Robert Lurie would accept the invitation and join Zell in Chicago as a partner in the newly-founded investment company Equity Group Investments. Zell and Lurie had a successful, complementary partnership in which Zell would source investment opportunities and envision the company’s long-term strategy, whereas Lurie, true to his engineering background, would focus on the details and intricacies of the company’s operations including building efficient systems for smooth operations and managing the company’s office environment. According to Zell, both partners’s skills complemented each other’s skills well, and the partnership was one in which “one-plus-one-equaled-eight.”

Since it’s early days, Equity Group Investments has been guided by the following investment fundamentals (as listed on the Company’s website):

- When everyone is going right, look left

- Operate on the condition of no surprises

- Ensure management’s interest are aligned with shareholders

- Sentimentality about an investment leads to a lack of discipline

- Nothing should stand between a company and its fiduciary responsibility to shareholders

- Everyday you’re not selling an asset that’s in your portfolio, you’re choosing to buy it

- Liquidity = Value

- Look for opportunities in markets with pent-up demand

- Look for good companies with bad balance sheets

- Take meaningful decisions so that you can influence your own destiny

- The definition of a true partner is someone who shares your level of risk

- Understand the downside

- It all comes down to Econ 101 – supply and demand

Throughout the mid-to-late 1970s, as interest rates remained high and real estate developers struggled with the overbuilding of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the real estate market crashed and the economy entered a recession. Zell and Lurie noticed opportunities and aggressively acquired distressed multi-family, retail, and office assets with a long-term plan of holding the assets for income. Over time, alluding to his tendency of acquiring distressed assets at bargain prices, Zell would come to be referred to as a “grave dancer.” To effectively implement their long-term approach to investing, Zell and Lurie created separate property management vehicles for each of the asset types, thereby creating a platform for which could sustain rapid growth.

Robert Lurie (Left) and Sam Zell (Right)

In 1976, Zell and Lurie began using the Equity Office name for the acquisition and management of their office buildings across the United States. Equity Office would continue its blistering growth during the late 1970s, continuing buying high-quality, distressed office properties throughout the country. Amidst the high inflation of the 1970s, the nominal value of Equity Office’s holdings increased significantly, providing Zell and Lurie with plenty of equity in their properties which they could use to borrow additional capital and continue acquiring new properties.

During the 1980s, EOP’s growth was limited as real estate fundamentals improved, commercial real estate prices rebounded, the number of foreclosures and delinquencies declined, and Zell and Lurie were unable to source enough opportunities to continue at their previous pace of acquisitions. Also, Robert Lurie’s two-year struggle with cancer and eventual death from cancer in 1990, was a very difficult time period for the company, in which communication between the partners was limited to just phone calls. Around the time of Lurie’s diagnosis, Zell would take on a larger role in operating Equity Group Investments.

During the early 1990s, in the midst of another recession, Zell continued his and Lurie’s contrarian investing approach by building up EOP’s real estate portfolio with high-quality urban assets, whereas most other investors had shifted their focus to suburban office properties. By 1996, Zell had built up an office portfolio valued at $4.8 billion, consisting of 32 million square feet in 90 buildings. That same year, Zell formed Equity Office Properties Trust, a real estate investment trust (REIT), which would hold all of the company’s office properties, while providing flexibility for the company to pursue a whole new level of growth as well as liquidity for Lurie’s estate and Sam Zell through sales of stock in the public markets.

In its market debut, Equity Office Properties Trust, sold 25 million shares at a price of $21, raising about $500 Million from a partial sale of the company’s equity. In the coming years, EOP continued its rapid growth through its 1997 $4 billion acquisition of Beacon Properties Corp and its $4.6 billion acquisition of Cornerstone properties in 2000. In 2001, Equity Office continued its aggressive acquisition strategy by acquiring Spieker Properties, a REIT with holdings concentrated on the West Coast, for $7.2 Billion. Following the Spieker acquisition, EOP was about three times larger than the next largest office REIT, Boston Properties.

During the early 2000s, Zell was confronted with EOP’s stubbornly underpriced stock, which Zell considered to be trading at about 25% less than the value of the company’s assets less liabilities. EOP’s lagging stock price may have been due in part to the lack of uniformity across EOP’s holdings, which ranged from billion dollar office buildings in New York City (which might be worth 25 times the property’s net operating income) to sub-$10 million suburban office buildings in Salt Lake City (which might be worth 12 times the property’s net operating income) to industrial properties in California (which might be worth 10 times the property’s net operating income).

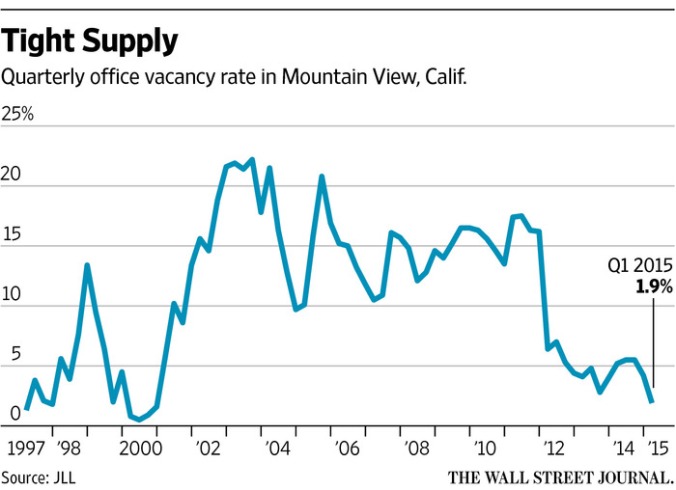

Another potential reason for EOP’s lagging stock price may have been due to EOP’s ill-timed, 2001 acquisition of Spieker Properties for $7.2 billion. Shortly after EOP’s acquisition, the vacancy rates in Silicon Valley, where most of Spieker Properties’ holdings were concentrated, would spike to over 20% within a year following EOP’s acquisition. As a result, in the following years Zell’s reputation as an astute, “buy low, sell high” investor was questioned, which may have also played in a role in the company’s lagging stock price.

Graph showing the sharply increasing vacancy rate between early 2001 and 2003, immediately follwing EOP’s takeover of Spieker Properties

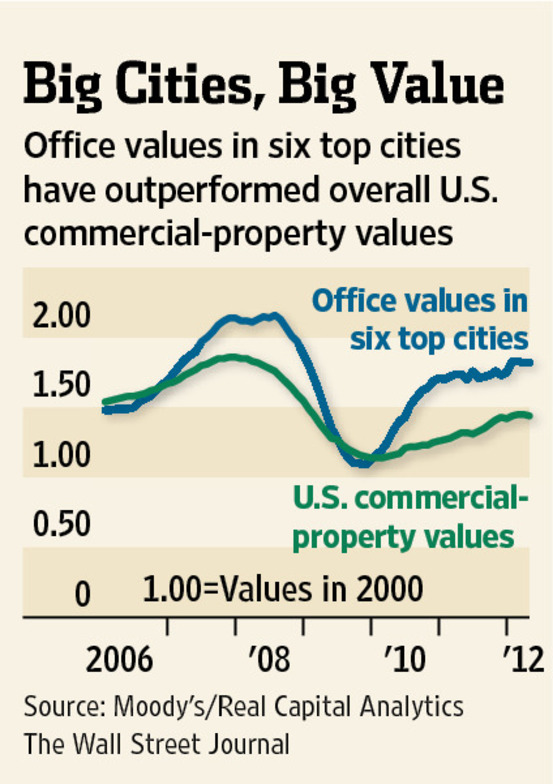

Regardless of the reasons or causes for EOP’s lagging stock price, during the early 2000s, EOP couldn’t justify raising money by issuing new stock at the undervalued stock price (which would dilute it’s ownership of the company based on the low price at which the stock was currently trading). Therefore, in the early 2000s, Zell attempted to create more consistency across EOP’s holdings by selling many of EOP’s office assets in smaller markets such as Salt Lake City, UT, Nashville, TN, and Charlotte, NC, and also selling many of EOP’s industrial buildings. Subsequently, Zell used the sales proceeds to acquire trophy office buildings in more urban, primary markets such as Los Angeles, New York City, Boston, and Washington D.C. This new strategy would end up increasing EOP’s value (not necessarily stock price, but value) in coming years as the urban markets, in which EOP’s holdings had become increasingly concentrated, experienced a sharp run-up in market rental rates and property valuations during the early and mid-2000s.

Graph from the WSJ showing office values in the top six cities significantly outpacing U.S. Commercial-property values

Despite the run-up in national real estate prices, EOP’s share price remained at about $30 at the end of 2005, about 25% less than Zell’s internal valuation of the REIT’s intrinsic value at the time. Despite Zell’s strategy of creating uniformity across EOP’s office holdings, the public market seemed committed to its undervalued view of EOP. Zell understood that current real estate valuations were generally excessive and also that real estate assets and REITs would certainly not maintain their current price levels in the coming years. This made EOP’s stock price susceptible a major decline, even if EOP’s stock price was currently priced below the value of its assets. Widely known as the “grave dancer,” Zell certainly knew how this ordeal was going to play out, and he was determined to play his cards right and exit at the peak of the real estate market.

The Negotiation

The hidden value of EOP’s holdings had long been known to Jonathan Gray, co-head of Blackstone. Specifically, Gray understood that many of EOP’s assets in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, and New York City were irreplaceable, trophy properties which would attain high prices if sold to local REITs, pension funds and sovereign funds who had long been eyeing some of EOP’s individual buildings. Within the past few years, Gray attempted to arrange buyouts of EOP with two separate partners. Most recently, in mid-2006, Gray met for lunch with EOP’s chief executive officer, Richard Kincaid, and asked whether EOP would consider selling the company. At the time, Kincaid responded that EOP would only consider a “Godfather offer,” (an offer that can’t be refused) which temporarily turned Gray off to the idea of acquiring EOP.

About six weeks later, Gray was meeting Douglas Kaplan, CEO of Douglas Emmett, Inc, owner of many high-rise office buildings in West Los Angeles. During casual conversation, Kaplan mentioned to Gray that if Blackstone were to acquire EOP, Douglas Emmett would be willing to acquire EOP’s West Los Angeles buildings at a low cap rate of 4 (about 25 times the net operating income of the buildings). This comment once again planted a seed in Gray’s head and caused him to mull another EOP bid. Further reassured by Blackstone’s success in its acquisitions of CarrAmerica and Trizec, a few days later, Gray reached out to EOP’s banker, who in turn advised Gray that an offer of at least $45 per share would be needed in order to attract EOP’s attention. Within a week, Blackstone submitted a preliminary cash offer for $47.50 per share, and shortly thereafter executed a confidentiality agreement to be able to thoroughly review EOP’s financials. After reviewing EOP’s financials, Blackstone reaffirmed its original cash offer of $47.50, and shortly thereafter agreed to a $48.50 counter from EOP, a price equating to a total value of $36 billion for Equity Office Properties Trust. Most importantly, Zell negotiated a low breakup fee of only $200 million, a fee not high enough to discourage other bidders from submitting offers on EOP and potentially starting a bidding war.

On January 15th, after sending mixed signals about its potential interest in submitting a bid on EOP, a second suitor, Vornado Realty Trust, called EOP to notify them that they would be submitting a competing offer. Vornado Realty Trust, a REIT headed by Zell’s long-time friend Steven Roth, had approached EOP to discuss a takeover bid earlier that year, which is one of the primary reasons Zell was insistent on negotiating a low breakup fee of only $200 million (breakup fees usually run 2-3% of a company’s market capitalization) during its negotiations with Blackstone. True to his casual, eccentric nature, Zell emailed Roth the following:

“Dear Stevie: / Roses are red / violets are blue / I heard a rumor / Is it true? / Loves and kisses, / Sam.”

Roth responded:

“Sam how are you? / The rumor is true / I do love you / And the price is $52.”

A photo of close friends Steven Roth and Sam Zell

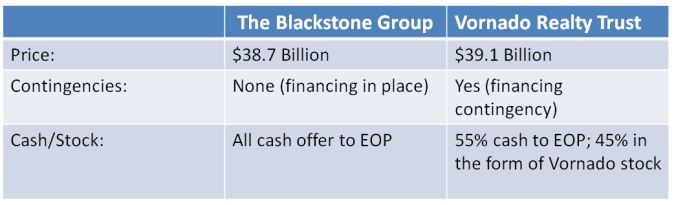

Vornado’s offer, which came out to a total of $38 billion was unappealing to EOP, because the offer included financing contingencies and also the offer consisted of only 60% cash, with the remaining 40% to be paid in the form of Vornado’s stock. Nevertheless, Zell was able to use the presence of a competing offer to encourage Blackstone to raise their non-contingent, cash offer to $54 per share, with a $700 million breakup fee to discourage other bidders. Vornado, then raised its non-contingent offer to $56 per share, consisting of 55% cash, with the remaining 45% to be paid in the form of Vornado’s stock. Blackstone then upped their offer to $55.50 per share for a total amount of $38.7 billion. Vornado withdrew their interest and Blackstone closed on its acquisition of EOP on February 7, 2007.

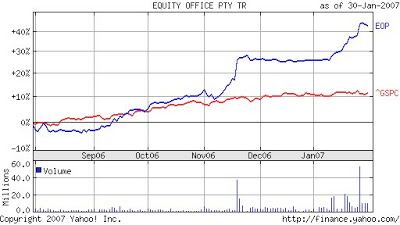

The selling price of EOP was over 50% higher than what EOP’s stock was trading for before rumors of a buyout surfaced. EOP certainly ended up receiving a “Godfather offer,” as Richard Kincaid, originally requested from Gray during their lunch. With some masterful negotiating, Zell had jumped ship at the right time, escaping a market downturn and more importantly attaining a sky-high price for EOP’s shareholders.

A line graph showing the % change in EOP’s stock price from August 2006 until until January 2007

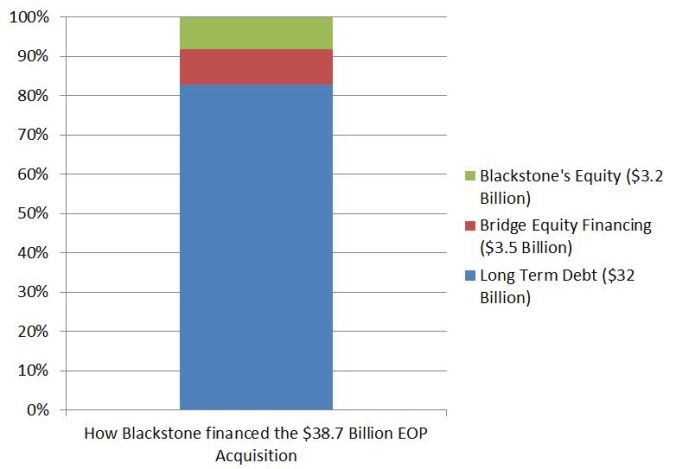

For Blackstone, however, work was just beginning. Blackstone had leveraged its buyout with $32 billion of long-term debt from Bear Stearns, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs, as well as an additional $3.5 billion of equity bridge financing. In all, Blackstone brought only $3.2 billion to the closing table, amounting to less than 10% of the total acquisition price.

Blackstone knew it had to act quickly in selling off many of EOP’s properties at high valuations in order to pay down its debt and reduce its overall risk before the inevitable market downturn. When recounting his conversations with Blackstone CEO, Stephen Schwarzman at the time, Gray recalled, “We talked about putting the firm’s reputation at risk in so big a deal. If we had overpaid and the deal had gone spectacularly bad, we could have really hurt a franchise that took twenty years to build.”

In the next post, we’ll review Blackstone’s historical sell-off in depth.

Lessons and Takeaways

Now, let’s go through some lessons and takeaways from the backgrounds of both companies and the negotiation process through which Blackstone ultimately acquired EOP:

Lesson 1: Nobody makes it big without intending to make it big.

In reading about Sam Zell’s beginnings in real estate, one thing that really stood out was Zell’s fixation on real estate investing from a young age. Even while studying at University of Michigan, Zell was already intending to be one of the major players in the real estate industry. Upon graduating, he told his friend and fraternity brother Robert Lurie that he was moving to Chicago with the plan of “playing on a big field in real estate.” Although this might seem trivial, this shines a light on the thinking of billionaire real estate investor. Many people plan on “working in real estate,” “trying to make a living in real estate,” or “testing the waters before jumping in.” Zell, on the other hand, knew he was entering the business to be one of the star players on the field. It’s this mentality that ensured that Zell was ready to take huge action when opportunities arose in the real estate market during the early 1970s, early 1980s, early 1990s, and early 2000s.

Lesson 2: The terms of a deal are often more important than the price of the deal.

During the negotiations with EOP, Blackstone was not the highest bidder for EOP but Blackstone still ended up as the accepted offer. Why? Because the terms of Blackstone’s offer were much more attractive than the competing offer from Vornado Realty Trust. Side by side, here is how the latest offers of each bidder compared:

Although Blackstone’s offer was lower than Vornado’s offer, most sellers would feel much more comfortable, secure, and confident with Blackstone’s offer which wasn’t relying on obtaining financing. Also, as previously mentioned, Zell was bearish on real estate and REITs in general. Zell reasoned that if he were to sell EOP, what good would it do him to exchange his ownership of EOP for ownership of another REIT which was just as likely to take a nosedive during a recession? Zell’s preference for cash proved to be a wise choice, as over the two years following the buyout, Vornado’s stock price would drop 80% (see below graph.)

A line graph showing the nearly 80% drop in Vornado’s stock price from February 2007 to March 2009

All in all, buyers should make an effort to learn about a seller’s intentions, goals, concerns, and preferences. Many times, buyers can easily gain advantages and increase the attractiveness of their offers, simply by playing with the terms of the agreement, which won’t necessarily be disadvantageous or cost anything for the buyer.

Lesson 3: Keep emotions out of deal analysis. If there’s enough profit in a deal at today’s price, then the deal makes sense at today’s price, regardless of the historical price.

Blackstone’s initial accepted offer for EOP was $36 billion (including equity and debt). For a couple of months, Blackstone remained the unchallenged and likely future owner of EOP. However, in January 2007 Vornado submitted its offer for EOP, and Blackstone either had the choice of walking away with the relatively disappointing $200 million breakup fee or to up its offer by about $3 billion above its original offer amount. For two months, Blackstone was feeling as if they would be able to acquire EOP at a price that would ultimately yield them $3 billion more in profit than they would end up earning at the $39 billion price. Faced with this disappointing turn of events, many investors would just focus on the “lost” $3 billion and be unable to get past how much higher the new price would be than what they were so close to acquiring the company for. Instead of thinking of what could have been, Gray thought about whether this deal could still earn a substantial profit for Blackstone. Gray proceeded to call local and regional real estate investors and have conversations with them regarding EOP’s assets. Which assets would they be interested in acquiring and for how much? During these conversations, Gray learned that based on the prices he was negotiating during the discussions, a price of $39 billion would still be doable. Gray deserves credit for maintaining the right frame of mind and not being discouraged by the $3 billion price increase, which shows the rational decision making which was central to Blackstone’s success during the negotiations.

Lesson 4: Real estate transactions are often win-win transactions

As previously discussed, during the early 2000s EOP was in frustrating situation, where its stock price was significantly less than the value of its individual assets. For many reasons, EOP wasn’t in a position to simply sell off EOP’s assets individually and distribute the proceeds to EOP’s shareholders in the form of irregular dividends over many years. If EOP were to embark on a 3-5 year selloff of EOP’s assets, shareholders would likely not appreciate the instability of the strategy, which would inevitably lead to shareholder anxiety and shareholders tirelessly working/guessing the value of EOP’s remaining assets after every quarter.

On the other hand, one of Blackstone’s main competitive advantages is that as a real estate private equity firm Blackstone can structure transactions in a way that many real estate investors aren’t able to. For example, Blackstone raises specific funds for private equity real estate investments which usually provide Blackstone with about 10 years before investor capital (including profits) must be returned to its investors. Investors in Blackstone’s funds are committed to a 10-year investment horizon, are aware of Blackstone’s opportunistic real estate strategy (which sometimes requires creative approaches to making a profit), and are not discouraged by short-term paper losses.

Another difference between REITs and private equity real estate companies is that REITs are primarily valued by their quarterly dividends, which incentivizes REITs to prioritize stable income rather than focusing on forcing appreciation of the REIT’s individual assets. Blackstone, on the other hand, is incentivized by generating an overall high return for its investors, which incentivizes both maximizing cash flow and value appreciation. Therefore, Blackstone would be in a much better position to invest large amounts of capital into EOP’s under-performing office buildings, thereby foregoing short-term cash flow, in order to achieve a much higher sales price.

Due to these differences, this transaction provided a profitable, attractive option for both EOP shareholders and Blackstone. EOP shareholders and executives were provided with the opportunity to sell their ownership position at a price much closer to the true equity value of EOP’s portfolio in a quick all-cash transaction at what many people perceived to be the height of the market. From Blackstone’s perspective, this transaction presented the company with an opportunity to take advantage of its flexible operating model by carving up EOP’s portfolio and selling assets individually, selling assets in smaller portfolios, or possibly even investing additional funds in some of EOP’s properties with the goal of maximizing the eventual sale proceeds.

All in all, just as Blackstone and EOP engaged in a win-win transaction, so too all real estate professionals should strive to understand each other’s situation, limitations, competitive advantages, etc. For one investor to profit, another investor doesn’t necessarily need to miss out on a benefit. Instead, by thinking about what assets, strengths and limitations each party brings to the table, both parties can walk away from a transaction with more than they otherwise would have.

Lesson 5: Understanding and taking advantage of market cycles can lead to huge profits

In building up and operating Equity Investments International, much of Zell’s growth and success can be attributed to taking advantage of the peaks and troughs of market cycles. For example, shortly after founding Equity Investments International, during the early 1970s Zell embarked on an aggressive buying spree. Zell’s acquisitions during the early 1970s likely multiplied in value as inflation and improving real estate fundamentals would work together to provide a huge boost real estate values.

We can gain a further understanding of Zell’s strategy by also noticing is actions when the market was overheated. During the 1980s, as distressed real estate opportunities were far and few between, Zell diverted his attention away from real estate to corporate private equity. Just a few years later, during the Savings and Loan Crisis of the early 1990s, Zell restarted aggressively acquiring distressed real estate opportunities. This strategy played a major role in how Zell was able to acquire real estate assets for a fraction of the assets’ previous value and for a fraction of the assets’ future value.

Lesson 6: In business partnerships, both partners’ skills should complement each other

Partnerships are very common in real estate investing, likely due to the capital intensive nature of real estate investing and also the multidisciplinary nature of real estate investing. Many real estate partnerships lead to massive success and lifelong friendships, whereas other partnerships end in bitter disputes and breakups.

Why do some partnerships endure while others end badly? Among other factors, an enduring long-term partnership must be one where both partners are better off because of being involved in the partnership. Each partner has skills, strengths, and contributions that complement the other partner’s skills, strengths, and contributions, leading to exponentially greater success working together than could be attained by working separately. Zell perfectly captured this idea, when he described his and Lurie’s partnership as “one-plus-one-equals-eight.” This concept is clearly displayed through Zell’s ambitious, deal-oriented, and visionary nature, combined with Lurie’s detail-oriented, efficiency-oriented, and more short-sighted view. These very different personalities worked together and complemented each other, building up one of the most impressive real estate companies in modern history.

Lesson 7: Don’t take “no” for an answer. No is just a suggestion, and setbacks are just stepping stones to success

Another lesson in this transaction can be learned through Blackstone’s relentless pursuit of EOP. During the courting and acquisition process, Gray displayed persistence and optimism in the face of repeated failures, rejections and setbacks.

Gray first two public attempts at acquiring EOP were unsuccessful. Soon after, while meeting for lunch with EOP’s chief executive, Gray was discouraged in giving an offer, when EOP’s CEO told him that they wouldn’t consider selling for anything other than a “Godfather offer,” in other words an offer that can’t be refused because shareholders would proactively take a stand to oppose EOP’s rejection of the offer.

Despite repeated setbacks and discouraging responses, Gray continued pursuing an acquisition of Equity Office Properties until eventually succeeding.

Lesson 8: Acquiring publicly-traded stocks at below intrinsic value is a potential profitable investment strategy

EOP’s undervalued stock price during the early and mid-2000s challenges the efficient market hypothesis, which states that it’s impossible to beat the stock market, because stock prices at any given time always incorporate all the information available at a certain time. Zell has been known to personally estimate the value of each of his individual real estate assets at least every 90 days. Based off of Zell’s estimates, during the early and mid-2000s, EOP’s stock was about 25% undervalued, trading at $30 per share, when the value of EOP’s assets less debt pointed to an intrinsic value of $40 per share. Blackstone clearly agreed that EOP’s stock was undervalued, as it paid price over 25% higher than EOP’s stock price at the time that it initially submitted its offer to EOP.

If an investor were to really understand the value of EOP’s assets during 2005 and the value of EOP’s individual office buildings, they could have profited greatly as the stock price would either eventually gravitate toward its intrinsic value or remain an attractive acquisition opportunity to private equity companies. Likewise, the same strategy can be applied to quality, viable businesses whose stock is being traded at a price below the intrinsic value of a company.

Sources:

http://egizell.com/index2.html

King of Capital Book

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blackstone_Group

http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/equity-office-properties-trust-history/

Love it!

LikeLike

Thanks, part 2 coming soon!

LikeLike

Pingback: How Blackstone Tripled its Initial Investment through its 2007 Buyout of Equity Office Properties – Part 2: The Selloff, Ownership Process, and Outcome | Behind the Deal

Pingback: New Player In Living Walls Brings Outside Inside | Your Mark On The World